Tighter silica rules needed to protect miners from black lung disease

It is well-documented that breathing in silica dust, also known as quartz, is a prime culprit in the ongoing epidemic of complicated black lung disease, but regulations protecting coal miners from this dangerous substance are weak. With one in five Central Appalachian coal-miners who have worked 25 years or more underground now afflicted with the deadly disease, the consequence of these weak worker protections can be measured in lives.

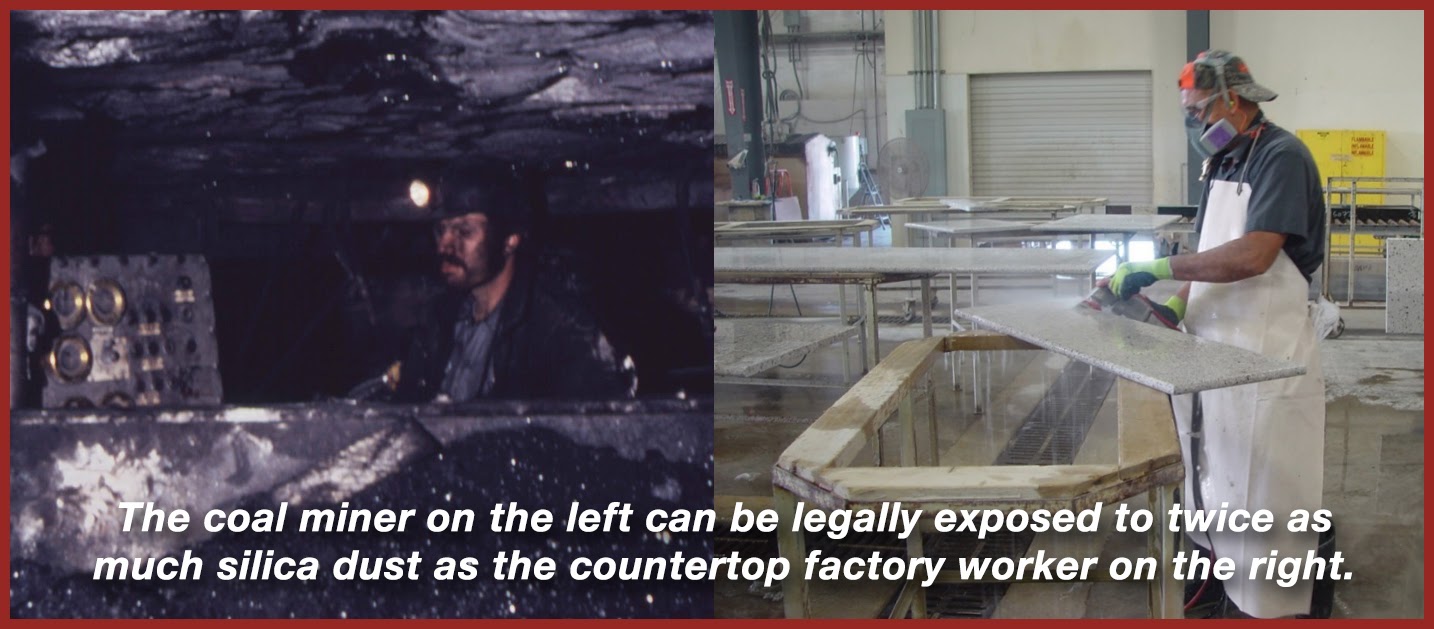

Currently, the Mine Safety and Health Administration allows miners to be exposed to as much as 100 micrograms of silica dust per cubic meter of air. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General both recommend that this level be reduced to 50 micrograms per cubic meter, which is the current legal level of exposure in all other industries. (You read that right. It is currently legal for coal miners to be exposed to twice as much silica dust as any other worker.) The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, a non-profit research organization, sets the recommended silica exposure level even lower, at 25 micrograms per cubic meter.

Miners are exposed to unsafe but legal levels of respirable silica during about 1 out of every 18 shifts, suggests a recent Appalachian Voices analysis of coal mine silica sample data. The analysis found that 7.35% of silica samples collected by MSHA since 2014 exceeded the 50 microgram per cubic meter limit recommended by NIOSH and others, while only 1.72% of those samples exceeded the current legal limit of 100 micrograms/cubic meter. Considering these numbers alongside the current spike in cases of black lung disease, it is easy to conclude that existing regulations are ineffective at protecting miners’ health.

In addition to the current silica exposure limit being too high, it is also difficult to enforce. Rather than directly requiring mines with unacceptably high silica levels to reduce those levels, current MSHA enforcement methods address silica only as a percentage of total respirable dust.

The way it works is this: if silica makes up more than 5% of a mine’s total respirable dust sample (which consists of coal dust plus silica and other particulates), then that mine is required to bring its total dust level down. This assumes that reducing the amount of total dust in the mine will also bring the level of silica into compliance.

The problem with that approach is that most coal mines currently operating in Appalachia require miners to cut through large amounts of sandstone, the source of silica dust. As a result, it is entirely possible for a coal mine to comply with even a lowered total respirable dust level, but still contain unsafe levels of silica.

Appalachian Voices’ analysis found 34 instances since 2014 when silica comprised less than 5% of total respirable dust, but exceeded the legal limit of 100mcg per cubic meter, and 337 instances when silica exceeded the recommended limit of 50mcg per cubic meter. This faulty enforcement mechanism and the too-high limit on silica dust mean that MSHA would not have ordered corrective actions on any of these occasions, even though silica levels were extremely high.

The United Mine Workers of America, Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, and others have been calling on the Mine Safety and Health Administration to strengthen these regulations for more than a decade. In recent years, Appalachian Voices became active in this effort in partnership with the Black Lung Association.

This growing coalition is calling on MSHA to lower the Permissible Exposure Limit for silica from 100 to 50 micrograms per cubic meter, which would grant coal miners the same protections as workers in every other industry. Miners and their advocates are also demanding that MSHA implement effective enforcement mechanisms targeting silica levels specifically, regardless of the levels of other types of dust in the mines.

Additionally, miners and their supporters are urging MSHA to improve enforcement of existing controls intended to keep dust down in the first place. Enforcement of these controls should be the primary strategy to protect miners, rather than overly relying on personal protective equipment, such as respirators, which can be difficult to properly use and maintain, and which unfairly makes the individual miner, rather than the mine operator, responsible for that miner’s safety. The many dust mask lawsuits that exist are evidence that it is not safe to rely only on personal protective devices.

Photo at left courtesy of U.S. National Archives, photo at right courtesy of U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

During the Obama administration, MSHA worked to address these issues. At that time, the agency was led by Joe Main, who had previously directed UMWA’s Health and Safety Department for over two decades. In 2014, Joe Main’s MSHA took actions that dramatically improved the accuracy of monitoring and enforcement of exposure limits for total respirable dust, improving safety conditions for miners.

Under Main’s leadership, MSHA had also been working on strengthening protections against exposure to silica dust specifically. But this process was incomplete when Donald Trump won the 2016 election, and Trump’s MSHA director, David Zatezalo, ultimately took no steps to protect miners from the dangerous substance.

In February, President Biden appointed Jeannette Galanis as acting assistant labor secretary overseeing the Mine Safety and Health Administration. Galanis had served as chief of staff to Joe Main during his tenure with the department, a sign that the unfinished efforts to improve silica regulations will now resume.